Name: Jen Rose

Lives: Suffolk - UK

Type of IBD: Ulcerative colitis; proctitis and distal colitis

Diagnosis Date: 1989

Symptoms at Diagnosis: Diarrhoea and bleeding, urgency and tenesmus, weight loss, fatigue, anaemia

Details of Surgery: None

I don’t really remember a time when I went from being well to being unwell. I just remember spending longer and longer in the toilet, particularly before school in the morning. In fact, without parental intervention, I likely would have stayed there most of the time (I would sneak a book in with me if I could!). It was my safe space. I had developed an overwhelming feeling of urgency that never seemed to go away. I was pale and thin, had constant diarrhoea, was losing blood (it seemed like gallons of it at the time) and felt permanently exhausted and drained. I was 10-years-old.

This was over 30 years ago now, so memories are vague in places. Alongside grown-ups of all ages, I was sent to the gastroenterology department in my local hospital. It was a pretty bleak and uninviting place. I don’t recall ever seeing any other children of my age there, though I’m sure there must have been. I remember endless incomprehensible conversations between my mum and the doctors and nurses, intrusive examinations and countless blood tests and procedures. I remember feeling frightened, overwhelmed, embarrassed and ashamed, and perhaps most clearly, a complete loss of control.

Shortly afterwards, I had a diagnosis. At the time I was simply aware that it was ulcerative colitis. I now know it to be proctitis and distal colitis (here I have to admit that it was only very recently that I actually understood what those terms really meant!). I had experienced my first colonoscopy, and I was told that my disease was moderate UC, tailing off to mild, and that I was ‘fortunate’ because of this. I didn’t feel very fortunate, and the symptoms that I was struggling with didn’t feel very mild to moderate. However, I was a small child being told this by important, highly trained and rather intimidating grown ups, so of course, I didn’t question it.

“I grew up with a general feeling that bowels, toilet habits and poo are not ‘nice’ subjects for discussion - they were words that were quite often spoken in hushed tones.”

I grew up with a general feeling that bowels, toilet habits and poo are not ‘nice’ subjects for discussion - they were words that were quite often spoken in hushed tones. This, along with my newly acquired belief that I was ‘fortunate’ and so shouldn’t make a fuss, was the beginning of my almost 30 year journey of embarrassment and shame, and endless attempts to downplay or hide my condition and symptoms. It never occurred to me to acknowledge that my normal was quite different to other people’s normal.

Rounds of steroids brought my symptoms under control fairly quickly, simultaneously I had my first experience of ‘moon face’, and other associated symptoms; this resulting in active avoidance of oral steroid treatment wherever possible in the future. At that point, I began taking (with the odd laziness break), mesalazine (Asacol), and have been ever since. On and off I would take iron tablets to combat anaemia (I didn’t really understand what that was either - why didn’t I question these things?). I felt a lot better, though I was rarely symptom free. I often wouldn’t admit that to anyone though, for fear of repeat colonoscopies and rounds of steroids. I developed a privately obsessive need to know at all times that there was an accessible toilet nearby, often spent long periods of time in said toilets (or visited them multiple times), and coped with bloating and gas, and the pain that resulted from holding that gas in!

“I felt that I was battling against a body that was letting me down.”

I became a quietly anxious, inwardly focussed child. I had much to cope with, but was unwilling to share how I was feeling (remember, I was fortunate!). As I grew I developed painfully low self-esteem, and began to blame myself for being broken. I felt that I was battling against a body that was letting me down.

I loved high school, but it was pretty tough. When I was flaring, which seemed to be most of the time at a level which I was learning to cope with, repeated trips to the toilet didn’t go down well with my teachers or my fellow students (eventually, and to my great embarrassment, school were informed of the nature of my condition after a particularly awkward history lesson where I had to leave to use the toilet twice, and was refused permission a third time). I wanted to be invisible, to fit in.

"I vividly remember sitting there, eyes closed, telling myself that I was disgusting, hating that I couldn’t control myself like other people could."

When I reached the toilet, despite having rushed there at top speed, quite often I was unable to go anyway. I just couldn’t shake that feeling of urgency (again, very recently I learned why this was). Sometimes I didn’t quite make it and would have to set about clearing up accidents. I never admitted this to anyone. On more than one occasion I would return to class without underwear, much to my well-hidden shame. And when I did need to go, often I would find myself sat for long minutes, holding on until the toilets were empty – my fragile self-esteem couldn’t risk the chance that someone would hear me. I vividly remember sitting there, eyes closed, telling myself that I was disgusting, hating that I couldn’t control myself like other people could. By the early afternoon, I would invariably have quite severe stomach pain from the gas that I had been holding in throughout the day. Again I told no one.

All the exciting things about school were accompanied by high levels of anxiety for me. School trips, coach journeys and sleepovers always involved risk. When I was 14 I took part in a French exchange, which involved staying with a lovely French family in their home. Of course my anxiety was high, and so my symptoms flared. I can still recall with surprising clarity the feelings that accompanied my attempts to explain, in not even quite GCSE level French (they didn’t speak more than a few words of English), why I was in and out of their toilet throughout the night.

"I had no one that I felt I could talk to about this, I didn’t know anyone else with IBD."

It makes me really sad to remember all this now, to think about the hard time I gave myself. I had no one that I felt I could talk to about this, I didn’t know anyone else with IBD. And of course, I was fortunate!

Managing my condition was a little easier as I approached adulthood and began to have more control over my life, although by that time I had developed chronic anxiety, had very low self-worth and was overwhelmingly risk-adverse. It didn’t occur to me that any of these might be attributable, at least in part, to my condition. It just felt like more additions to the long list of my own failings. I sought help on various occasions when the anxiety was overwhelming, was prescribed antidepressants, and a bit of CBT counselling. But, no one ever made the connection, helped me to understand why I might be experiencing these difficulties. I sometimes question why I didn’t take the initiative to help myself more, why I didn’t speak out and demand answers. But deep down I was still that fearful 10-year-old, and my ingrained coping strategy was to dissociate - to pretend with every bit of energy that I had that I was ok, even to myself, and accept that this was how my life would be now, that there was nothing I could do.

So life moved on, I lived my normal. Over the years I had three beautiful children. Then a few years later my marriage ended. I knew that I was unhappy and that something needed to change, but I didn’t know what to do about it. Then one day I met a wonderful woman (who is now a very dear friend) who encouraged me to seek counselling. At this point I still had no idea that a large proportion of what I was struggling with could be directly connected to the impact of my IBD. Gradually, over many months, this started to become clear to me.

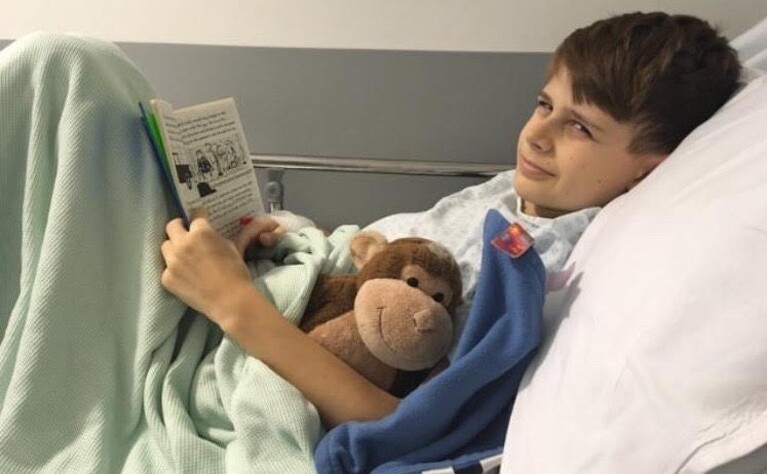

Around the same time, about two-and-a-half years ago, my middle child began feeling unwell. Max has a diagnosis of high functioning Autistic Spectrum Condition (ASC), and would already display a range of unusual behaviours. When he started sitting down on the floor at every opportunity; in the shops, out walking, on the playground in the rain, I just thought it was another to add to the list. But then he began losing weight, had developed dark shadows under his eyes and was tired all the time.

“Then he began to complain of a bubbly tummy. And then going to the toilet more often. And I knew.”

Then he began to complain of a bubbly tummy. And then going to the toilet more often. And I knew. Our GP, who readily accepted that I knew what I was seeing in Max, sent us to the hospital, the same department I’d spent time in 30 years ago. Max was examined, then it was suggested that we should give it three months to see how he got on. Thankfully, we received an unexpected appointment at Addenbrooke’s Hospital the following week, as I was seriously concerned that three months would be far too long, considering how rapidly Max’s condition was deteriorating.

The team at Addenbrooke’s were and are incredible. After a range of tests and his first colonoscopy, Max received his diagnosis. Crohn’s disease. My heart broke briefly.

But then I knew what I had to do. It was my job to make sure that Max would never feel the way I had felt. Talking about his condition without shame or embarrassment would become the norm. Most importantly, it was vital that he never felt alone. And so, bowels, toilet habits and poo became a celebrated topic of conversation in our house! Max seemed completely comfortable talking about his condition, and so I encouraged this. Right from the start, we loved our trips to Addenbrooke's, and Max was always happy to see the team. He was incredibly strong. Despite my concerns, blood tests, procedures and various medication changes were all taken in his stride, as were rounds of steroids (and moon face!). When his symptoms weren’t controlled by steroids and Azathioprine, the next step was biologics (Adulimumab). It’s not his favourite moment of the week, but Max has adapted to regular injections (he now self-injects) and his symptoms were quickly brought under control. He started growing again!

Max has been doing really well since, and as far as I can tell there has been little impact upon his emotional wellbeing from his IBD journey so far. Addenbrooke’s, and his school have been extremely supportive. Last year we were contacted by Seb and the team at IBDrelief, which resulted in Max sharing his experiences in information videos produced for CICRA. Watching those films at CICRA’s family day in London was such an emotional moment for me. Max would never struggle in the same way I did.

After meeting Seb during Max’s filming, and hearing about his experiences, I was totally inspired - I wanted to focus more upon educating myself about my condition. I began to learn more about how my body works, and what an incredible thing the digestive system is. I’ve shared my story, and my awareness of the impact that IBD can have on a person’s emotional wellbeing. I have learned about, and taken on positive lifestyle changes, in order for my body to be in the best place it can to deal with the challenges it faces. It feels like I’ve stopped fighting against my body, and instead am learning to love it. To take back control of my own health.

“I have begun to appreciate the true power of connection. Of being heard.”

Seb also encouraged me to see the value in my journey; that perhaps I can use my experiences to help others. I found the confidence to begin training to become a psychotherapeutic counsellor, and alongside CICRA, am offering emotional support to newly diagnosed IBD patients and their families. I have found my purpose. And rather wonderfully, it all stems from the very thing that has been the biggest challenge of my life so far.

Above all, I have begun to appreciate the true power of connection. Of being heard. I’m not ignoring the possibility that things may get tough again. I’m ready for that, should it happen. But would I change my journey? Absolutely not. Now, I truly feel fortunate.