Name: Usayd Siddiqi

Year of Birth 1998

Lives: Houston, Texas

Type of IBD: Ulcerative colitis

Diagnosis Date: 2018

Symptoms at Diagnosis: Blood in stool, sudden urges, and constant bowel movements

Details of Surgery: 2 stage J-pouch surgery with ileus and blockage complications

Thanks to ulcerative colitis, a chronic disease, my early 20s have been a humbling experience. Days where I’ve had 20 bowel movements, times when I found nothing but blood in my stool, and worst of all, embarrassing mishaps such as an incident whilst snowboarding!

I remember swiftly descending the slopes of Wilmot Mountain in Wisconsin, when suddenly, I felt my stomach rumble. “Just have to make it down,” I thought to myself. The urge intensified instantaneously so I quickly unstrapped my boots from the board, sprinted towards the restroom, and barged into the first stall. But I was a few seconds late. As I sat on the toilet seat, I stared down at the dirty floor and my soiled diaper. After an hour filled with tactical manoeuvres and funky positions, I was all cleaned up and ready to go.

This was my first solo trip and it almost never happened. After I had parked my car at the airport, I had started feeling an urge. I tried resisting it, but for the umpteenth time, I couldn’t, and I ended up relieving myself. Right then and there. Under the night sky. Amid thousands of cars. I then headed to the terminal not to catch my flight but to cancel it. But then a visceral thought engulfed me. “Will you allow your life to become a s**t show?” At that moment, I decided I would never allow my circumstances to deter me from living the way I want to.

I was diagnosed in 2018, when out of the blue I had noticed blood in my stool. A colonoscopy confirmed what my doctor suspected. Although my symptoms were manageable early on, having an official label of a chronic disease under my name did send shivers down my spine.

I was lucky to have a healthy support system of family and friends that always kept my spirits high. However, my real test came when my symptoms worsened with the number of bowel movements, sudden urges, and weight loss going out of control and medications failing. Sulfasalazine, mesalamine, Entyvio, Stelara, and Remicade all failed to improve my health. I even tried alternative medicine like naturopathy and Ayurvedic medicine as a supplemental form of treatment, but the issues remained, and I decided it was time to take a leap if I wanted to improve my lifestyle. I eventually underwent surgery, which became a month-long roller-coaster ride filled with twists, torture, tribulations, and toughness.

“ I was in good spirits. Hopeful. Excited. Fearless. Little did I know what was to come.”

On March 22nd 2021, around the crack of dawn, my dad drove me up to the hospital in the quest to begin my healing journey one last time. Besides feeling bloated thanks to the four litres of bowel prep I had drunk, I was in good spirits. Hopeful. Excited. Fearless. Little did I know what was to come.

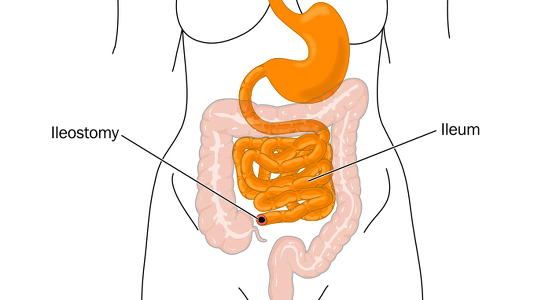

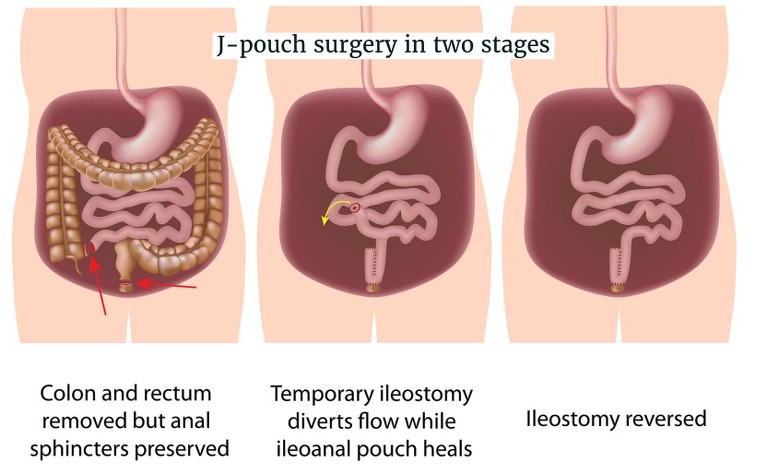

The J-pouch surgery, also known as ileoanal anastomosis, is a two-part surgery. In the first part, the colon and rectum are removed, a pouch shaped like the letter J is constructed using the end of the small intestine and connected to the anus, and a temporary ileostomy is created to pass stools. The second stage occurred approximately two months later. At that point, the ileostomy was reversed, so I could pass stools normally.

I can still recall the first time I felt nervous. It was when I was asked to sign some papers before entering the operating room. A mere formality, you'd think. But as I quickly skimmed through four pages of potential risks, the last one caught my eye. DEATH. Written just like that. Bolded and all in capitals. A large reason as to why I wasn't too bothered about this procedure was because I knew the situation was out of my control. I told myself, "If anyone should be nervous, it should be the surgeon". Luckily, I didn't have too much time for second thoughts as I was rolled towards the operating room for my epidural. Thanks to anaesthesia, that's the last thing I remembered.

About eight hours later, I remember waking up in the recovery room and being denied water. I could make out someone with a thick Indian accent speaking with my dad over the phone. And then I took a pill and was knocked out. Four hours later, I remember looking around in a different room and being assessed by a nurse. Or maybe it was two hours later. And maybe I didn't take a pill. This was the beginning of how I would lose sense of time and whether events actually took place or were just a figment of my imagination.

A team of doctors came in the morning and let me know everything went smoothly and I could start on a liquid diet. After having fasted for the most part of two days, I gulped down whatever was provided to me. And that's where the pain began.

“Heavy painkillers such as morphine provided a catch-22 solution since they would alleviate the misery but also delay the awakening of the intestines.”

Because of the heavy dosage of anaesthesia, my intestines had fallen asleep and I was diagnosed with a paralytic ileus, a complication that occurs approximately 20% of the time when you’ve had this procedure. As a result, nothing was passing through and I experienced severe cramping. And when I say cramping, this isn't like the muscle cramp that occurs due to dehydration during a game. I was constantly moaning in agony. A nasogastric tube was inserted to suck all the liquid I had taken along with the fluids the stomach produces. Heavy painkillers such as morphine provided a catch-22 solution since they would alleviate the misery but also delay the awakening of the intestines.

“To recover from an ileus, there was nothing I could do besides wait”

To recover from an ileus, there was nothing I could do besides wait. Reoperation was the last resort. My surgeon came in and decided to take a proactive approach. Throughout this time, I had a nasogastric tube covering my face, a Foley catheter to drain urine, a central intravenous line providing me nutrition and electrolytes, and an ostomy bag to collect stools from the stoma, which is the portion of the intestine sticking out temporarily from the abdomen. At this time, I also learned that I had a red Robinson catheter placed inside my stoma in an attempt to relieve the obstruction that tends to occur because of edema, which is swelling caused by excess fluid, being at the level of stoma. This edema tends to be a common cause for the ileus. I don't recall what exactly was done since she gave me a drug diminishing my senses but after some tinkering and replacing the tube with a thicker one, stools began to gush out. Mission accomplished.

After some frustrating events such as being fed double contrast resulting in extreme nausea and passing blood through my backside which almost induced a heart attack, I was discharged in a few days. The greatest moment came when the nasogastric tube was removed. Not only did it mean things went down to my stomach and not to a container, but it also meant I could tilt my head towards the ceiling for the first time in two weeks. Peas for a meal were disappointing but at least I felt free.

“Six hours went by and the diarrhoea stopped. A good thing you'd think. But that's when the pain returned.”

On April 4th, I woke up to stool flowing out of my bag. I quickly called my dad to take me to the shower and assist me in changing the ostomy bag. But the stool refused to stop gushing out. After some time, we got things settled and I took an anti-diarrheal medication that was given to me to take as needed. Before this, I had only been nibbling on food, but I finally had an appetite and was able to have a full meal. Two French toasts to be exact. They tasted weird. Six hours went by and the diarrhoea stopped. A good thing you'd think. But that's when the pain returned.

As time passed, I groaned more, shrieked louder, and prayed nonstop. Besides having a blurry image of some family friends dropping by, I can't recall anything. I had spent the weekend lying in bed, with a beanbag and multiple pillows keeping me upright. My surgeon suspected it was the anti-diarrheal medication causing the pain and she suggested giving it about two days for the medication to leave my system.

"On the third day, the level of pain became intolerable.”

However, it wasn't because of the anti-diarrheal medication. The effects didn't wear down and the discomfort only increased. On the third day, the level of pain became intolerable. There had been no stool since the Sunday morning episode. This was worse than the cramping during the ileus. My surgeon told me to rush over for a CT scan. After spending over half a day waiting at the ER, the results showed a blockage and I was readmitted. Worst of all, the nasogastric tube was back on my face.

As I mentioned earlier, re-operating is the last thing physicians desire as it opens the door for more complications. More tests such as contrast studies and X-rays were done since they couldn't pinpoint the exact issue and speculated it might be a recurring ileus. The idea with a contrast study is that the liquid potentially forces its way through the intestines, at the same time potentially unblocking the blockage. But the issue is if it doesn't pass through, one feels nauseated and vomits. That's what happened on two occasions with me. The X-rays had me screaming in anguish as cold boards were slid under my body and I was forced to lie straight.

“Walking became almost impossible because of the cramps.”

The pain became more torturous day by day. Every second felt like an eternity. Walking became almost impossible because of the cramps. There was even a day where I was unable to move my left shoulder. An attempt was made to insert a tube from the other end of the intestine to mitigate the suffering but that just made it worse. It was only once heavy opioids such as oxycodone and Dilaudid became available to me at the push of a button that I stopped screaming the name of nurses.

After one last CT scan was administered on the fifth day from my readmission, a team of doctors came in during the middle of the day and decided it was time to head to the operating room. Except there was one last twist left in the tale. Around Christmas time, my family had caught Covid-19. Although we were lucky to not face any life-threatening circumstances, the positive test would end up haunting me. Before the surgery, I was required to take a routine test but shockingly, my result came out positive. I panicked but luckily, I was asymptomatic and since I had tested positive within 90 days, it was adjudicated that I had developed antibodies to the virus and the surgery wouldn’t have to be delayed.

However, as the doctors were prepping for me in the operating room this time around, it came to their notice that I had tested positive a day ago. Along with that, there was a record of occasional nightly fevers during vital checks in the last week. After X-rays and blood and urine tests came out normal, they determined COVID-19 as the cause for the fever. Thus, I was labelled symptomatic and not allowed to enter the operating room since anaesthesia and Covid-19 is a lethal combination and can result in cardiac arrest. To take that risk would be considered malpractice. The staff said I would need to isolate on the 10th floor along with the other Covid-19 patients for 10 days and then be re-evaluated before I could head to the operating room to treat the small bowel obstruction. It looked bleak but hope remained because the final decision was to be made by an infection specialist the next morning. So, we waited.

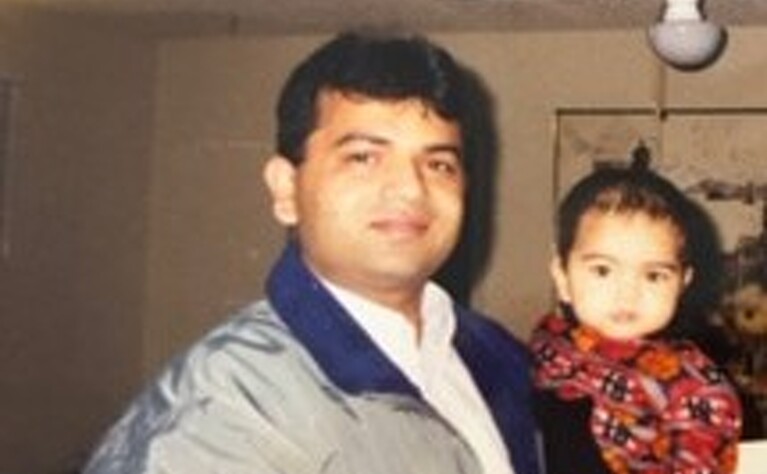

I say "we" because this was a battle I didn't fight alone. Due to the pandemic, visitation guidelines meant only one visitor was allowed and it had to be the same visitor. And although I had the support of my family and friends through messages, it was my dad that held my hand when I needed it most. He would drive more than 30 minutes daily to just see me battle away. I don't know how it feels to be a parent, but I could only imagine the restlessness a father would feel being so close yet so helpless seeing his kid in indescribable, uninterrupted pain. I don't even recall half of his visits since I would have my eyes closed and just be fighting off pain. But he reminded me to stay strong. To believe that better days were ahead. To never give up because I hadn't gone through all this just to quit. To pray that my sins were erased, and afflictions eased. But even he broke down that night.

I had never seen him cry but that night, as he held my hand knowing it might possibly be for the last time, he let it all out. Moments I'll never forget. Moments so powerful that they change a person's outlook on life. The tone in the doctor's voice made it seem there was no way they were going to risk an operation under the current circumstances. But imagining 10 MORE days of this pain that was intensifying by every tick on the clock brought me chills. And what if the fever remained and my test results still came out positive after the isolation? And what if I really had the virus and my COVID-19 symptoms worsened? I hadn't been seeing my friends or the rest of my family but now, I wouldn't be able to even see my father? What if I didn't make it?

“The physical pain had been excruciating but now the mental toll had taken the situation to a different level.”

The physical pain had been excruciating but now the mental toll had taken the situation to a different level. I still remember that night, sweating profusely, and staring at the clock all night. It was the first night of Ramadan and I remember thanking the heavens that I had made it to this blessed month. Because if there was any time a Muslim would like to die, it would be Ramadan. I prayed for a miracle.

Once I caught glimpses of the sun, my eyes drifted from the clock towards the door. A few hours after I had begun to grow impatient, my nurse came in and told me I was on the docket for surgery later in the day. I was puzzled since the specialist had never come in to check in on me. The additional tests at night also were not in my favor. But I wasn't complaining. Yet, I also didn't want to start counting my chickens before they hatched.

Eventually, the specialist doctor came into my room to let me know that I needed the surgery ASAP and that I most probably didn't have COVID-19. It took a while for my number to come as multiple procedures were scheduled before mine. But I remained patient until I was taken to the waiting room. That's where I became restless since I was without my painkillers. A nurse stumbled into my room and we gazed at each other before he lifted his mask and I recognized him. An old friend of mine who wasn't aware of my situation spoke with me for some time and lifted my morale before my anaesthesiologist and surgeon showed up.

I woke up about six hours later as I was being transported back to my room where I remember babbling some gibberish to my favorite nurse and my personal care assistant (PCA) whom I had developed quite a friendship with. I was perplexed when I saw the clock had gone past midnight since I felt it had been less than an hour.

The next morning, my surgeon, who I should mention is such a kind and composed individual, updated me. Unlike the first surgery when a laparoscopy was sufficient for her to access my bowels, the reoperation forced her to cut me up. After opening me up through a T-shaped cut, it was found that there had been an infection on the previous stoma which radiologists couldn't detect from the umpteen tests they had done. This infection had been causing the fever that was being attributed to COVID-19. She suspected the infection came about by a perforation she had possibly caused by the tinkering she had done with the tube a few weeks ago that had resolved the issue of the ileus. The obstruction didn't occur right away as it took time for the bacteria to build up which explained why I felt the pain a few days later. At least now I had achieved symmetry, thanks to a stoma sticking out on each side.

The cramping had subsided but now there was a new element of pain as the cut right down the middle of the abdomen and across the waist had pretty much immobilized my abdominal muscles. Laughing, coughing, sneezing, and hiccupping caused tremendous pain. But as time went on, the body began to heal. The surgery team expected another lengthy ileus but to everyone's surprise, 24 hours is all it took. I'll never forget the moment when my nurse, who was doing a routine check before leaving for the day, ecstatically yelled, "There's poop!".

“As challenging as this condition has been, I’ve learned priceless lessons.”

As challenging as this condition has been, I’ve learned priceless lessons. Humility has been a natural consequence of incontinence. Flare-ups have taught me life is fickle and death is inevitable. Consequently, my relationships and religiosity have progressed to the next level. I’ve also learned to be grateful for the little things and empathise with other people’s struggles.

However, the most valuable trait I’ve acquired is resilience. Before this affliction, I knew I could persevere through tough times whether it was recovering from fractured facial bones suffered in a varsity basketball game or bouncing back from failing thermodynamics. However, ulcerative colitis has taught me that life is about making the most of your cards rather than complaining about the hand you’ve been dealt. The physical pain coupled with the mental battle of abstaining from my favorite homemade Indian dishes, plus seeing my muscles dwindle, missing out on family dinners, checking the disability box at work, and knowing there is no light at the end of the tunnel at times implores me to give up. Yet, I wake up every day and make a choice to not only conquer the trials and tribulations this illness throws at me but to keep chasing my dreams.

Although the last two months at home presented their own challenges from craving painkillers to leaking ostomy bags to relying on others for basic needs, I was in a much better place, functioning independently and being able to complete most tasks. I was to have my reversal surgery, the second and final stage of the J-pouch surgery. I hope I can get back to peak health and put this chapter of ulcerative colitis to bed.

"I hope that every time life throws a curveball at me, I can use this experience to remind myself I can get through anything."

As Nietzsche said, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger”. Lessons abound from this passage of my life and I hope that every time life throws a curveball at me, I can use this experience to remind myself I can get through anything. It's also a reminder for all of us that nothing is guaranteed so cherish every little moment and don't push off your quest for greatness to tomorrow.

The first stage of my surgery ended up being one of the more complicated cases you’ll see, and I hope it inspires you rather than frightens you. Because I’m still standing. The second surgery took place July 9th 2021 and went smoothly with no complications. I was discharged from the hospital three days later.

I am very hopeful. And in some time, when I’m back to full health, playing sports and traveling the world, I will look back and say it was all worth it.

For anyone dealing with IBD or any severe health issue, my advice is to take this challenge on and remind yourself that greatness has a price. Let the disease teach you the lessons of life. Yes, there will be times where you want to just give up and throw in the towel, but you have to fight through and tell yourself, you will not let your life be a s**t show.