Dr Lindsay Bottoms is currently carrying out a study entitled 'Can exercise help improve quality of life in Crohn's disease' with funding provided by Crohn's & Colitis UK. As a fencer with Crohn's disease the subject of exercise and IBD is something that is close to her heart. We asked her to tell us a bit more about the study, how it came about and what we currently know about exercise and IBD...

A: I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease when I was 14-years-old (in 1994) and to be honest I can’t really remember what it is like to be ‘normal’. I remember when I was first diagnosed that I had lost a lot of weight as it became too painful to eat. As a kid the easiest solution was to stop eating and this seemed to help a lot. Bizarrely, it never really stopped me playing sport which is what I spent most my time doing.

It took a while for the doctors to realise I had Crohn’s disease - I think I was one of the first kids on the Isle of Wight to be diagnosed with it. Now, as we all know, the prevalence of the disease has increased drastically especially in children. I blamed my BCG injection for years for my Crohn’s as I developed my first symptoms two weeks after the injection. But, as with other vaccinations, I think it was just co-incidence as it is a common age to develop Crohn’s; but also it might just have been my trigger. Either way, I was predisposed to having it.

I remember spending a year without playing sport as the doctors thought this was the best thing for me to do to get well ‐ that killed me! Thankfully, after a strong course of steroids my Crohn's went into remission. It took a good few years before it came back. We started to believe that I never actually had the disease! It was only when I went to university that it resurfaced. I suspect it was the emotional stress of moving away from home and a change in lifestyle that triggered it, but who knows!

It never really went back into remission, it would constantly come and go and I just learnt to live with it. It was part of my life to have pain, and so I carried on with normal life playing sport and studying.

Between 2008 and 2012 I was hospitalised quite a few times due to the stricture which had developed, and eventually I succumbed and had surgery in 2012 to have a bowel resection. It was during this period of time that ironically my fencing really became good and I trained a lot harder and I started to represent Great Britain at World Cups and also went on to fence at the fencing Commonwealth Championships in 2010 in Australia.

It was such a mixed emotional time, I had some incredible highs and equally some lows. But I never gave up on my sport (I even ran a marathon in the middle of a flare up), it was what kept me sane and gave me a good quality of life. I ended up having 1/2m of my small bowel removed in 2012 and thankfully because I went into surgery fit, they did not give me a stoma. Apparently, it was the only reason I wasn’t given one.

When I was recovering I read a lot more information about the disease. Until that point, I had stuck my head in the sand and ignored the fact I was ill. I took a three month research sabbatical from work when I had the surgery so I had a lot more time on my hands when I was recovering which enabled me to read a lot more about the disease.

I read a lot of leaflets that suggested that patients with Crohn’s should not do much exercise. If they felt they were capable of it they could go for a gentle walk at lunch time. I found this incredible, especially as I was aware that for other diseases such as cancer, diabetes and depression they were now recommending exercise for improved quality of life and even GPs were prescribing it.

I had just competed in a national open in fencing five weeks after my surgery having lost 12kg in weight from bed rest. I must confess, my specialist did advise me against doing it because it was probably too soon”¦I am not suggesting this is what people should do!! It absolutely killed me to do it, but I managed to protect my ranking and stayed in the top 10 in the UK with the result. I therefore, decided I wanted to do some research into the benefits of exercise in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

I did a literature search on exercise in inflammatory bowel disease and realised there was very little research available. What little research that had been performed was based on walking exercise and also recall information about physical activity. There was no conclusive evidence to suggest exercise would be beneficial.

When I went back to work, I was chatting about this to a colleague who is a pharmacologist and who has ulcerative colitis (UC). He started to explain to me about the differences in immune responses to Crohn’s and UC and how exercise could influence this. I then went away and started reading exercise immunology textbooks and realised that the immune response to exercise could potentially influence the immune response to both Crohn’s and UC in a positive way, but maybe through different exercise modalities.

This was when I saw the research grant call on the Crohn’s & Colitis UK website and decided that I wanted to create a research study to investigate my theory. So that is how it all came about. I chatted to my consultant at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital about the idea, and he was keen to get involved.

So, I suddenly had a research team and we put together the proposal. Unfortunately, we weren’t successful with our first attempt but they gave us really good feedback which we went away and addressed and we were successful the following year. For once I was really rather grateful for having Crohn’s disease!!!

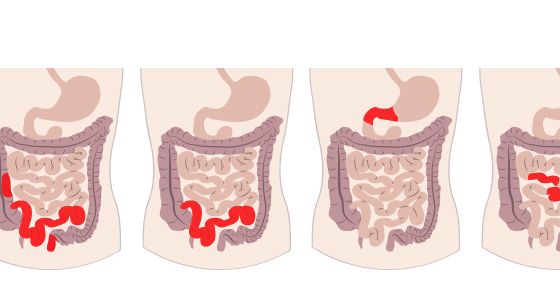

A: The pathology of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) is slightly different and therefore may respond differently to exercise, and as such our study is only focusing on CD (sorry UC people!!).

Currently, there is little published research on the safety and effects of exercise training in CD, however some authors have stated that light to moderate exercise will benefit patients by improving their quality of life as well as reducing stress levels, supporting weight management and increasing immune function and bone mineral density1.

The purpose of our study is to assess the feasibility of a larger-scale trial investigating benefits of exercise training in adults with mildly active or remitted CD. Two commonly-used exercise programmes are being assessed in our study ‐ high intensity interval training and moderate intensity continuous training. Some authors have questioned the appropriateness of high intensity exercise in individuals with IBD on the basis that it may cause negative effects such as gastrointenstinal distress2. However, there is little evidence to suggest high-intensity exercise is inappropriate in CD, and there are several high profile examples of athletes who suffer from IBD such as Sir Steve Redgrave.

High-intensity interval training has been the subject of interest in recent years in the fields of elite sports performance and clinical rehabilitation, as it may produce improvements in fitness and health outcomes superior to volume-matched moderate continuous training, with less time spent training. Being able to exercise over a shorter period of time may be more appealing to patients and promote compliance in this group.

Moderate intensity exercise has been observed to reduce cardiovascular risk in individuals3, therefore the current UK guidelines for physical activity for 18-65-year-olds stipulates that individuals should undertake moderate physical activity five times a week for 30 mins to improve health and well-being.

Moderate intensity exercise has also been shown to improve the immune system and help protect individuals against infection4 by increasing Th-1 lymphocytes5. This response would result in exercise not being able to help with the inflammation of the disease as Crohn’s disease is widely thought to be a Th-1 mediated disease.

Previous research investigating low to moderate levels of physical activity found patients were able to cope with exercise6. In addition, the other benefits of exercise, as previously mentioned, such as improving depression and bone mineral density will mean there is some improvement to the well-being of the patient with moderate exercise.

There is thus potential that certain exercise regimes that could potentially be beneficial for Crohn’s patients. Furthermore, exercise of a longer duration than 60 minutes has been shown to reduce Th- 1 cells5 which could be more beneficial for the inflammatory response.

However, exercise of this duration can have the potential to be associated with gastrointestinal distress2. Establishing a shorter duration exercise producing Th-1 cell reduction favourable immune response could be beneficial for Crohn’s patients. In recent years it has come to light that performing very short bursts of high intensity exercise (30-60s) followed by 30-60s rest repeated for 4-10 minutes has produced increased fat oxidation and increased maximal oxygen uptake7.

Furthermore, research has suggested that high intensity interval training (HIIT) can promote anti-inflammatory effects during recovery8. If this type of exercise could produce a reduction in Th-1 cells and produce an anti-inflammatory effect it could be of benefit in Crohn’s disease.

In addition, being able to perform exercise over a shorter period of time may be more appealing to patients and promote adherence to the exercise regime in this group. This was the idea behind our study and the research questions on which it was based. But before we can really start answering the questions we need to answer the question 'is it safe and feasible for patients to perform both moderate and high intensity exercise'.

A: The study we are currently doing is a feasibility study to answer the safety question as mentioned above. We have two recruiting training sites, one is based at the University of East London and the other is based at the University of Winchester. Patients are recruited from areas where they can access either university.

Patients (with mild or remitted CD between 16 and 65-years-old) who are recruited all complete an initial fitness test to determine their baseline fitness levels. All the exercise is performed on a bike. Following this they are randomised into one of three groups.

One group is a control group (just usual care and therefore does no exercise), another does high intensity interval training and the final group does moderate intensity exercise.

The exercise groups all undertake supervised cycling three times a week for 12 weeks at one of the university locations. The moderate-intensity exercise session involves 27 minutes of stationary cycling at a power output that elicits 35% of their maximum capacity.

The high intensity exercise sessions will be “volume-matched” to the moderate sessions, and will involve 60 seconds of stationary cycling at 90% capacity followed by 60s at 15% and repeated for 20 minutes (a total of 10 minutes of exercise). This approach has been shown to be safe for sedentary individuals9.

The training sessions are all supervised and therefore the patients are closely monitored. All participants receive fitness tests at the end of the 12 week training period (in week 13). There are blood samples taken at baseline, at the middle and end of the training for markers of inflammation.

Then after a further 12 weeks they receive a telephone interview to see how they are doing and whether they are exercising. The following outcome measures are assessed at baseline and three and six months after randomisation: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (IBDQ), the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index, a general wellbeing questionnaire, and the hospital anxiety and depression questionnaire. Feasibility outcomes will include rates of recruitment, retention, exercise adherence and acceptability.

A: We are still open for recruitment for our study and will be so until half way through 2017. So we are still welcoming volunteers with open arms!! The main eligibility criteria is that you can access either the University of East London in Stratford or the University of Winchester regularly as this is where the supervised exercise sessions take place.

In addition, you have to be between 16 and 65-years-old and have Crohn’s disease. I know there are already quite a few people who are currently exercising, but we can only recruit those who are doing less than 90 minutes of purposeful exercise a week as we want to see what adaptations occur with doing exercise.

If you are already exercising these adaptations may have already occurred. If you are interested in taking part, please send me an email to: l.bottoms@herts.ac.uk and I can give you more information and also put you in contact with our research assistant.

I would like to thank Crohn’s & Colitis UK for giving me this opportunity to be able to research a topic that means a lot to me. I genuinely believe exercise is beneficial for us who have inflammatory bowel disease and really believe it can help improve our quality of life.

Hopefully, if the feasibility study is successful, we can apply for further funding to continue our research and roll it out across the country. This will increase the participant numbers and enable us to get a much better understanding of the response to exercise in patients and the impact on their quality of life.